A dozen (or so) learnings from 15 years of software incident management

How to get great at solving problems you never want to encounter

As a software engineer, dealing with incidents sucks. Getting that on-call page at 3am on a Saturday morning? It can be dread-inducing, soul sucking and altogether an abhorrent episode. If it happens frequently at your workplace, it can quite literally induce PTSD.

Unfortunately this is a part and parcel of the software zeitgeist. If anything, these are the fires through which real engineering gets forged. These incidents teach you how to architect hardened systems, and in many cases, how not to.

This article goes into 2 aspects of how to deal with software incidents

🛠️ The practices that one needs to instill in their software platform and teams to prevent and learn from these experiences.

🧘 The attitude one needs to have to be resilient, and come away from these experiences not only unscathed, but with more than they went in.

The topics we will hit up are —

Automate your systems as much as you can

Tracking leading vs lagging indicators

“Actionable” Alerts should be self evident

Establish clear call chains and escalation paths

Empower front lines to make big decisions

Not all incidents are created equal

Resolve first, ask questions later

Make sure one person is in charge

Communicate clearly and frequently

Blameless post mortems are crucial

Followups to the post mortems are crucial

Incidents are not bad as long as MTTD is low

Humor is the great equalizer

Let us dive in for some details!

Automate your systems as much as you can

You really want to minimize how many incidents you learn either through your customers or through some severe accounting discrepancy days or weeks from when the incident started. While “automation” is an overused word in engineering, this is one of those areas where you truly want to find the right balance of signal to noise ratio and ensure that you and your team receive alerts without needing any human intervention.

If there are too many things to pick from, go super high level. What is the highest level metric you could pick? The one if the component systems fail to work as expected, will deviate from the norm? This could be tracking revenue flowing through the platform (for an e-commerce, financial or $-based platform), or number of current active users (for social media platforms). If you see the numbers crater or drop by a standard deviation or two, immediately alert the dev team. Focusing the first (or most important) alerts on the pulse of the business or the core user experience, is going to be a great metric to monitor. As you get more sophisticated and understand the system better, you can start to go deeper down the stack from an observability standpoint.

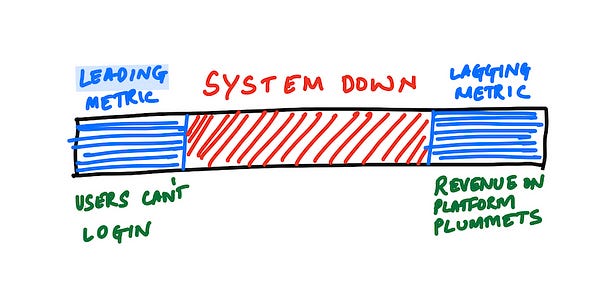

Tracking leading vs lagging indicators

Leading indicators are predictive in nature and are likely to point to an issue about to happen whereas lagging indicators are post-hoc and are representative of the aftermath once the issue is well in progress. If you can tap into the leading indicators (such as say “Session duration” starting to go down) in addition to or in place of lagging indicators (such as say “number of orders placed plummeting”) you can likely avert something that is pretty catastrophic.

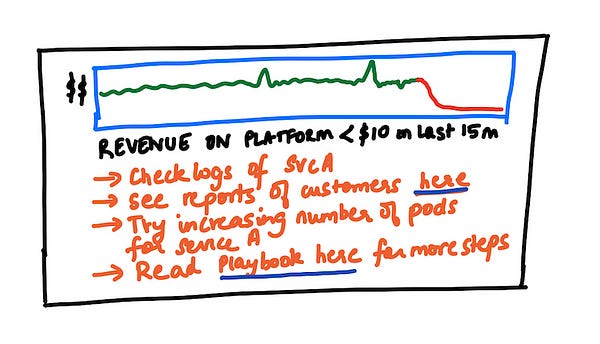

“Actionable” Alerts should be self evident

Your alerts must be self-evident so that it is crystal clear what next steps to take when they get fired. Whether it is to ascertain the severity of the issue, or to troubleshoot the incident, or remediate the issue, there should be enough details associated with the alert. You want to ensure it doesn’t require a lot of upfront discussion to determine what to do with the alert. You could stick these details in the content of the alert itself, or if its fairly verbose, you could link out to a runbook(s) that the team maintains for these type of issues.

Establish clear call chains and escalation paths

Have a clear outline of what happens when an alert fires, including who it gets routed to based on things like service ownership, timezone awareness etc is critical to ensure rapid response. Beyond that immediate first line of defense, it is also equally critical to ensure there is clarity about how and who to, the incident responder could escalate the incident. Often times if the issue is complex or far bigger in scope than one person can handle, it might be necessary to pull in more senior folks (or multiple people on the team) as well as cross-functional stakeholders. Making all of that easily accessible through tooling (like PagerDuty, OpsGenie) or crystal clear documentation (run books, wiki pages, repo READMEs), might be the difference between a catastrophic incident or a nothing-burger.

Empower front lines to make big decisions

While you need clear escalation paths, you don’t want that to be the default response. You must empower the first responders to be able to take real action to stem the bleeding or make on-the-spot decisions for remediation, without needing to consult senior management. This is both good for the company in terms of limiting fallout as well as for the employees who are giving a high responsibility that they are trusted to make big decisions. Reduce the red tape and increase the agency of individuals.

Not all incidents are created equal

Along with things like call chains and escalation paths, one other piece of collateral that is important is an incident priority scale. This is typically a quick reference for the first responder or the incident commander. It helps them quickly identify what the severity of the incident is and label it as such because it might warrant different grades of responses. Differentiating between critical incidents (like system outages or financial data corruption) and minor issues (such as color palette glitches) is essential for responders to avoid false alarms. It also ensures the team’s response remains effective and focused.

Resolve first, ask questions later

Without question, one of the most important things to do is to resolve the incident as quickly as possible. You do not want to spend time philosophizing why something happened or how it could have been prevented, while the incident is underway. You can reserve that for the post mortem. For the moment, just ruthlessly focus on resolving the incident and ask the tough questions later.

Make sure one person is in charge

Sometimes incidents can get too big. They touch too many services, they span multiple business domains, or they are just really impactful in terms of revenue or reputation. Thats when it is absolutely crucial that there is one person appointed to “traffic cop” the entire incident. At Place Exchange, we have instituted “Incident Commanders” who are a small group of people who are trained in complex incident response. The reason it is so important to have this kind of a role, is because when there are multiple parties involved, someone needs to be directing the traffic. Oftentimes engineers will start going down rabbit holes about the complexity of the problem or trying to understand how to solve the problem.

The role of the Incident Commander is to keep the focus of the group on rapid incident resolution. They make sure that everyone has a bias to action and while side investigations might be important, ensuring forward momentum is even more important. They are also responsible for ensuring that there is clear and constant communication with both internal and external stakeholders and partners. Incident commanders typically will start a synchronous line of voice communication, like a Slack huddle or a Google Meet meeting. This ensures that the folks crucial to the resolution of the incident are in constant contact. It is amazing how effective this small thing is compared to just allowing people to solve things async using chat. Incident commanders are also responsible for ensuring there is clear delegation for tasks that need to get done and make sure there is accountability for getting back responses or outcomes for those tasks. As they say, if you ask 2 people to feed a horse, the horse dies. An incident commander prevents that from happening and ultimately is responsible for the swift resolution of the incident.

Communicate clearly and frequently

People will often forgive their favorite app or software down, if they are being kept apprised of how the team is working hard at resolving the incident. Trying to keep things hidden either because you don’t feel you have a complete handle on the incident, or you and your team feel embarrassed about it, are no reasons to stop the communication from flowing outwards. Make sure the communication is concise, frequent and transparent to both your internal and external partners as that will help build goodwill.

Blameless post mortems are crucial

Post mortems or post-incident retrospectives are important to build a culture of learning and they absolutely must be blameless. Be critical of the process not the person. No one is harder on themselves than the person(s) who might have caused this and you gain nothing from flagellating them in public. If anything, all research suggests that you actually lose by doing this. The folks at Etsy are much better at talking about it, so go read https://www.etsy.com/codeascraft/blameless-postmortems if you want to learn more.

Followups to the post mortems are crucial

While conducting post mortems by themselves are important to build awareness and the feedback loops to learn from these incidents, the action items that are discussed to prevent these from happening in the future, are maybe more important? If the group has identified a set of gaps or vulnerabilities in the system, it is super important that there is focus and attention to resolving them in a timely manner to prevent the same issue from happening again. Its hard to prevent incidents from happening, and that is generally a tough conversation with your business and customers. But if the same incident happens over and over again, now that is both way harder to defend and indicates a severe problem in the health of and skillsmanship of the team.

Incidents are not bad as long as MTTD is low

Everybody gets it. Even the business people get it. Building software is HARD and in a world where all of our software has 100s of 1000s of dependencies, where the fault lines might crack is impossible to predict. Shit will hit the fan and it is OK. We can’t prevent incidents from happening. However, what really helps is to make sure that the MTTD for your incidents is really low.

Mean Time to Detect (MTTD) is a key performance indicator (KPI) that measures the average time it takes for an organization to identify an incident or security threat. It is hard to generalize, given the business domain, severity of impact etc, but if you are able to reduce your MTTD to seconds to minutes you are likely going to be able to significantly reduce the impact of an incident versus say it was hours to days (let alone weeks or months, which unfortunately is entirely possible).

Humor relieves you of the pain in the moment

All of this is so SERIOUS! Money getting lost! Customers having a terrible experience! However, in the midst of it all, I have found it to be critical to have a sense of humor. We shouldn’t forget that everyone is a human in this process and is going through varying degrees of stress. Injecting doses of humor at appropriate junctures helps relieve some of that pressure. It builds a sense of camaraderie that makes the team feel like they are in it together rather than they are off on an island in hell.

That’s a wrap. Thanks for reading!

⭐ If you like this type of content, be sure to follow me or subscribe to https://a1engineering.substack.com/subscribe! ⭐